We often hear the phrase ‘the union sold us out’. Especially if we work in a unionised workplace, we may be the ones who say it. Everything changes as soon as the official unions, of which we have become members in the hope that our conditions will be better, and perhaps even had to fight for their authorisation in the workplace, sit down at the bargaining table with the boss on our behalf. We have seen and experienced countless examples of unionists agreeing with the bosses behind closed doors and presenting even the conditions they have already settled for as a victory. But why do they do this, how do they achieve this despite us, and what can we do against it?

The reason is… Unionists are not workers, even if they have a labour background. Therefore their interests are not the same as ours. They don’t live our problems, they are the bosses or managers of a business somewhere out there called a “Union” and we are their ‘’work‘’. Some of them may do their jobs better, but their interests require that the bosses and workers be reconciled and that the union structure be maintained by any means necessary. Unions, like all capitalist enterprises, are hierarchical. So sometimes the lower level bureaucrats who are in closer contact with us may have to act in accordance to our wishes, they may even understand us and be angry with the top bureaucracy of the union and defend our demands as if they were one of us, but in the end they are part of the bureaucracy, the top managers of the enterprise will make the final decision, and they will often avoid confrontation with management in order to protect their own position. What functions in unions is a system in which those who enter it adapt to it. Those who get involved in the union wheels, even with good intentions, become part of it.

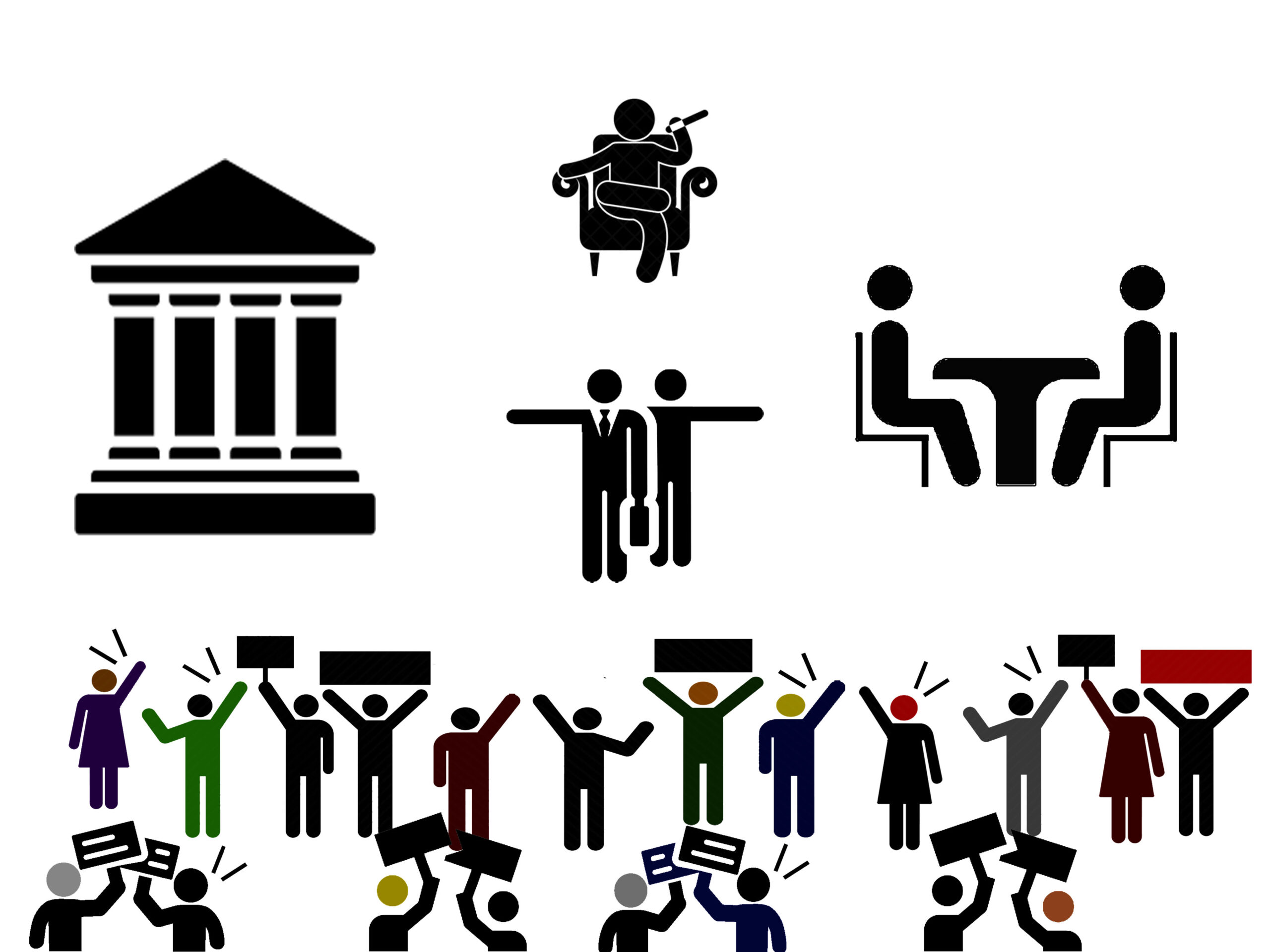

But how do the unions operating with workers’ dues, which would not exist if workers were not members, manage to convince or persuade us to accept the worst conditions? In fact, when we think about it, we can see that this situation is valid for the whole social structure. Without our consent, today’s society could not be sustained in this way. But we cannot eliminate this corrupt social order on our own. Individually we are only the cogs that maintain this mechanism. This also applies to the unions we are members of. When a union negotiates with the bosses or their representatives in a workplace, enterprise or group of workplaces, it is not only negotiating with the bosses on behalf of workers, it is also negotiating with workers on behalf of bosses. If we do not have a strong unity to defend our demands, it is easy for it to convince us one by one and to exclude those of us who are not convinced.

In some workplaces and in some periods they don’t take an interest in the collective bargaining processes of the majority of workers. In periods when workers are dissatisfied with the existing conditions, grumbling begins. In such cases unionists have to show that it is in the interest of the workers to remain members of the union. In this case the unions have the task of persuading the workers to accept the boss’s conditions. To do this they resort to tactics such as dividing the workers, prolonging the process, fait accompli, manipulation and putting pressure on the workers who stand out.

Unions exist in theory to bargain with the bosses on our behalf and to go on strike if necessary. However, legal limits render unions dysfunctional for us. It is these legal limits that unionists often use as an excuse to avoid effective struggles such as strikes. Indeed, what unions can do is limited by law. For example, if a friend of ours is fired, the union cannot propose anything other than a lawsuit. Or a political issue that affects our lives is never a concern of the unions. The only authorisation granted by law to the unions is the limited right to strike and collective labour agreements. And this is almost a right on paper. In order for a union to actually take a legal strike decision in a workplace, the protracted collective labour negotiations between the union and the employer must end without an agreement and various procedures must be fulfilled. In most cases, the decisions to strike get prohibited. The few union strikes that are put into practice often do not lead to the desired result, due to the fact that their time and conditions are determined by planning and compromise.

Another ‘right’ granted to unions is to bargain for the determination of the minimum wage. Together with representatives of the bosses and representatives of the government, Türk-İş, the confederation with the largest number of members, and its affiliated union representatives take part in the Minimum Wage Commission, which assembles once a year in the name of workers. The unions also pretend to bargain on behalf of us in this light comedy stage in which the state plays the role of neutrality. However, neither the state is neutral, nor the unions negotiate for our interests. As a result, the governments, which represent the interests of the bosses, always determine the minimum wage for us in any way they favour, in line with the interests of the bosses.

For public sector labourers’ unions, the right to strike does not even exist on paper. In fact, public labourers, who did not have the right to strike by law until 2001, carried out very serious de facto strikes, mass and militant street demonstrations throughout the 90s. Even this example from the recent past is a lesson that shows that unions restricted by laws are nothing but shackles for struggles in the workplaces.

When unions first emerged in different parts of the world, especially in Western Europe and the USA, they were not legal institutions. For this reason, although they were subjected to oppression and violence by bosses and states, they were very effective as instruments of workers’ struggle. As workers made achievements through struggle despite all oppression, bosses and states realised that it would be more effective to control unions by making them legal institutions. Professionalised unions, whose activities were regulated by law, became institutions that reconciled bosses and workers and put workers’ struggles under control.

On the other hand, the development of unions in Turkey took place at a later date. Although there were workers’ struggles in the late Ottoman period, these were very limited. After the Republican period, although the number of workers increased year by year, unions did not emerge as a necessity of the workers’ struggle, but were created by the state and functioned to promote statism and nationalism among the workers. Until the 1960s, there were almost no effective labour actions. After 1960, the unions continued to be under the control of the state and capital, the struggles that emerged after this date were tried to be controlled by the unions at every opportunity in favour of the bosses and the state.

It would not be correct to say that all unions are the same. Some unions are more like a department of the workplace, some have people with good intentions, some smaller unions are more like a political organisation or a solidarity association than a formal union. So we can engage with some of them to a certain extent, sometimes we can use unions in the same way as we use the courts or other legal institutions. And with some unions we have to fight tooth and nail, as we do against the employers. But what we must bear in mind is that our organisation is not the unions and that relying on the unions to solve our problems is no different from relying on politicians in parliament. We must not forget that when we do so, we will be handing over our struggle to them, in which case the unions will sell us out sooner or later.

Being unionised does not mean being organised. Whether we work in a workplace where a union is authorised or not, it is our unity in the workplace that will enable us to achieve our goals as workers. Unlike unions that see the struggle in the workplaces as limited to economic demands and collective labour agreement processes signed every 2-3 years, we need workplace associations that will enable us to fight together against all kinds of economic and political problems, from the simplest to the most complex, at every moment of working life. Only with the informal associations we will form in our workplaces can we improve our living and working conditions, produce policies for our own problems, change the balance of power in favour of the bosses in our favour, and ultimately break the wheels of capitalism, which means exploitation and domination for us.